The Mortgage Rate Road Map May Get You Lost

Why the idea that mortgage rates will follow the fed lower may leave you scratching your head.

Now that Fed Chair Powell almost guaranteed the beginning of Fed rate cuts, many believe a decline in mortgage rates is sure to follow. I’m not convinced. I think some structural changes may have occurred that will prevent this from happening in the way most expect. Additionally, those who manage our economy are employing some new tactics that they may choose to leverage to intentionally keep mortgage rates from the expected decline.

The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee is responsible for setting the “Fed Funds Rate,” the one interest rate over which the Fed has direct control. This is the rate banks charge each other to borrow funds. From this rate, the market sets the yields along the yield curve. It’s essential to understand this: the Fed is not directly responsible for setting interest rates (or mortgage rates), only the Fed Funds rate, also known as the “overnight rate.”

In previous rate cycles, as the Federal Reserve cuts the overnight rate, longer duration rates follow lower. This is the most common assumption in the mortgage industry during this cycle. The industry believes that not only will mortgage rates fall with the overnight rate, but there is also a widely held belief that the spread between risk-free rates and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) will narrow and come back in line with historical standards. Until “quantitative tightening” (QT) began in 2022, the typical spread between risk-free and MBS was about 70bps. That spread widened considerably during the past few years, at one point reaching several hundred basis points. This spread is currently more than double its historical average. I also believe the expectation that this spread will return to the pre-QT norm is overly optimistic. More on this later.

With the Who (mortgage industry) and What (mortgage rates will follow overnight rates) established, let's discuss Why I believe the market will frustrate those who think a meaningful drop in mortgage rates is imminent.

Famous Last Words: It’s Different This Time

While it has become a bit cliche to say, “It's different this time,” it is.

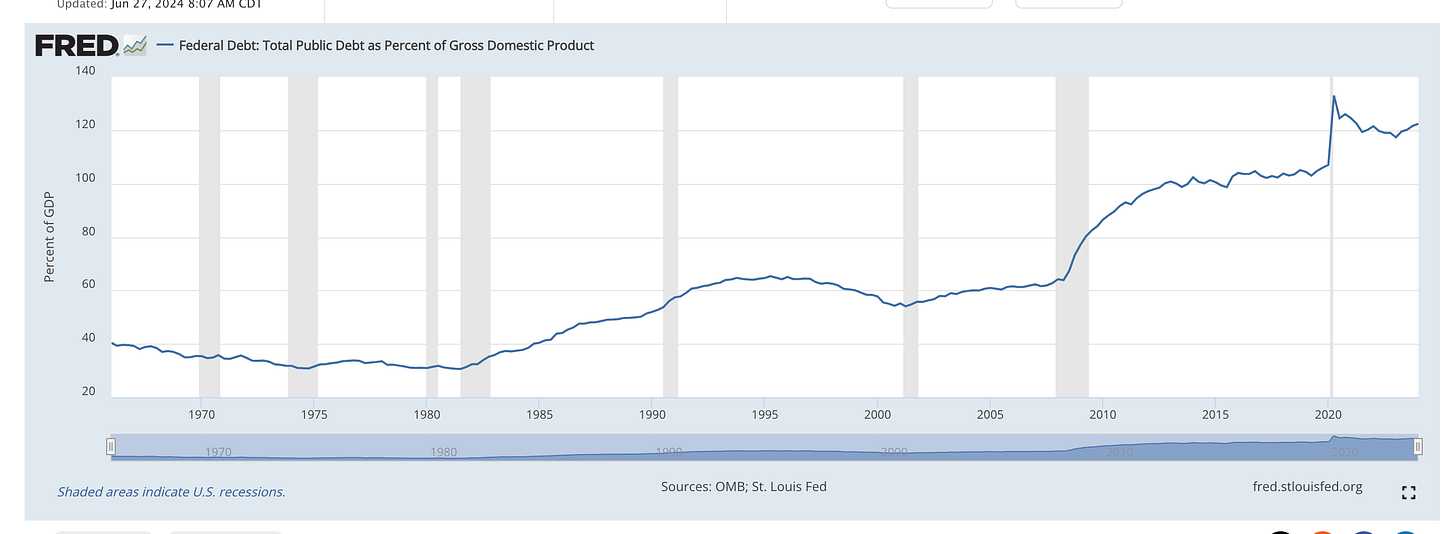

The most obvious is unprecedented levels of government debt. Debt to GDP is more than 120%. After hovering around 100% for most of the 2010s, this number has increased by 20% in just four years, the largest increase since the GFC.

With no reprieve in sight, as both political parties have discovered promises funded by deficit spending equal votes at the ballot box, some projections show that U.S. debt to GDP will rise to more than 170% by the early 2050s. Bond investors don’t want to get caught without a chair when the music stops—those who invest in debt need to have confidence that their debt will be repaid as agreed. U.S. debt is currently considered the safest debt for investors; however, if policymakers and politicians continue on this unsustainable path, investors will be likely to re-price the safety of U.S. debt - particularly longer term debt.

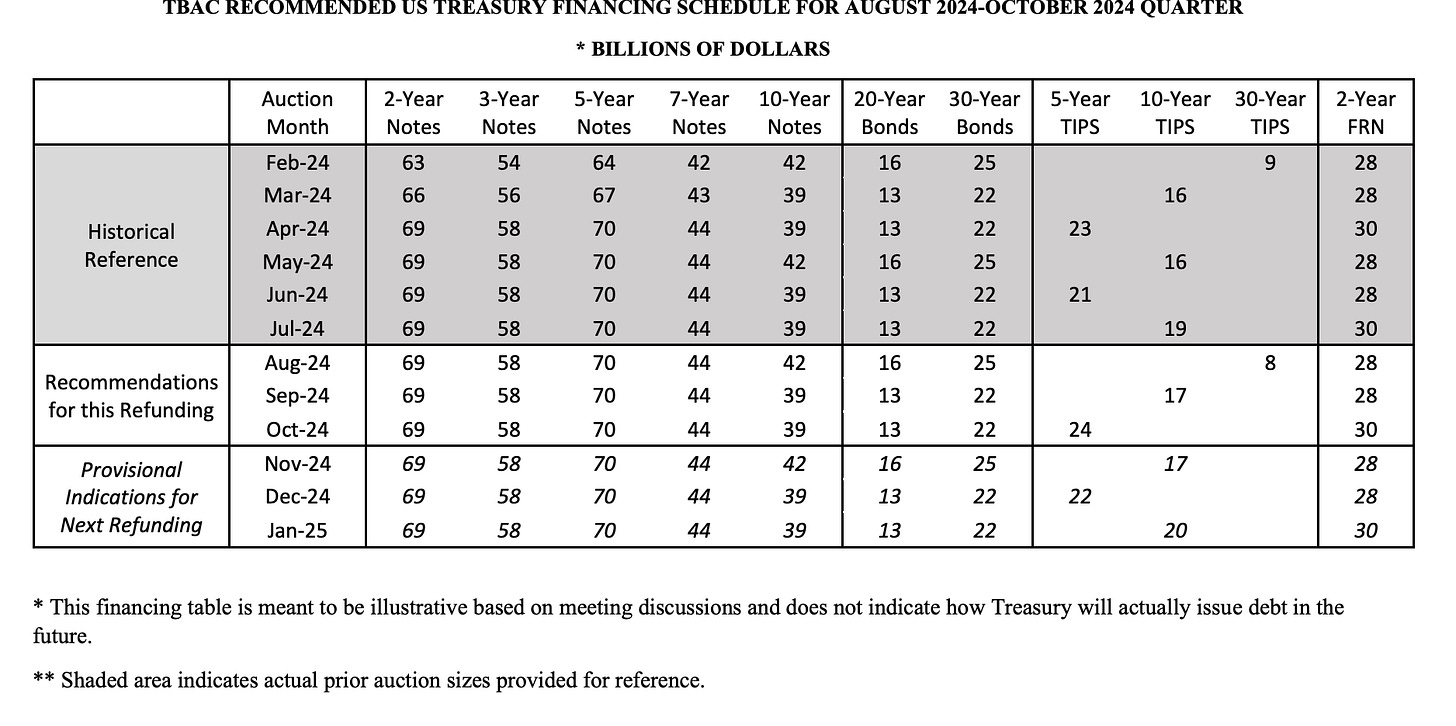

Beacuse of the unsustainability of current spending, investors are more keen to participate in the short-end of the curve, which is yielding a healthy 5%. This is one of the reasons the U.S. Treasury has adjusted how it issues new debt in the last few years, issuing more debt at the short-end of the curve.

Since QT began in 2022, the U.S. Treasury has quietly made some minor but impactful changes to how it issues new debt. These changes are in the tenor (duration) of new debt issued. The Treasury is leaning heavily on the front end of the curve, issuing most new debt in 5 years or less.

By controlling the mix of new issuance this way, the Treasury has been executing a form of defacto yield curve control, putting its thumb on the scale of the “free market” and exploiting the most fundamental principle—supply versus demand.

A recent paper dubbed this “ATI” (Activist Treasury Issuance.)

This would go a long way in explaining why the yield curve has been inverted for an unprecedented amount of time. Issuing more supply at the front end helps keep shorter-term rates higher through abundant supply and longer-term rates lower through scarcity. Recently, some experts have considered that the 10-year Treasury yield would likely be 25bps - 50bps higher if not for this tactic. The question then becomes, where would the Fed and the Treasury like long-end yields? They have demonstrated they are able and willing to influence the curve to achieve the desired outcome.

Also, an unusual tactic is being deployed in the form of Treasury buybacks. This is an effort to avoid liquidity problems in the bond market. Liquidity problems, as we saw at the onset of the COVID pandemic, can wreak havoc on markets and cause large, unexpected, and undesirable swings in yields. Earlier this year, the Treasury began doing buybacks of “off the run treasuries” and redeploying in new “ on the run” Treasuries. This provides a bit more demand and increased liquidity for new issuance. Nothing would be worse for rates (or policymakers) than a Treasury auction that garners no bids.

The point is that the Fed and the Treasury are working to control the yield curve in new ways. Secretary Janet Yellen once said that she believes recessions are now avoidable, and she is and will continue to do all she can to prove that point.

An Uncharted Path?

While the Fed's influence on the short end of the curve via the overnight rate is nothing new, the Treasury's influence on the shape of the curve is new and perhaps experimental. The Treasury is toying with the ability to peg rates where it sees fit through supply in ways it has never done before. Imagine a scenario where the Treasury can take advantage of demand along the curve to push out a little more new issuance.

Appetite For Debt

While the Fed has virtually guaranteed that they will begin cutting the overnight rate in the weeks or months ahead, and the Treasury will certainly continue to influence the shape of the curve, bond investors may also have something to say.

Bond investors may decide the front end of the curve has more appeal and less risk. With yields on the front end still hovering around 5%, why would investors choose to take convexity risk on the long end? If investors had more appetite on the short end and less on the long end, this would help produce something known as the bull steepener. A bull steepener is when the long end of the curve stays elevated ( or moves higher) while the short end of the curve falls—producing a steepening yield curve.

In this scenario where long-end rates stay elevated despite the Fed cutting, long-end Treasury rates remain elevated, mortgage rates will also stay elevated, and the “re-fi boom” the industry promised will fail to materialize. I believe this scenario has the highest probability of this scenario, although it may not happen immediately. Often, it takes the market a bit of time to digest new information and assess the long-term. The long end of the curve may fall along with the overnight rate, only to reverse the other way. This would likely produce higher rates on the long end as the market tends to make big moves on reversals.

Pace of Rate Cuts

Now that the Fed has basically committed to beginning its rate-cutting cycle, the debate has shifted to “How much?” and “How quickly?” The Fed may not be as eager to cut if it weren’t for a slowing labor market. Equity markets remain at all-time highs. I found this tongue-in-cheek tweet from

summed up this view well:Corporate earnings are not collapsing and money continues to pour into markets despite what I consider “stretched fundamentals and valuations”. GDP remains positive and unemployment remains reasonably low. The jobs market is slowing, although not in the dire straights we often read about. There was an overstatement of job creation over the past 12 months. It should also be clear that the recent revision is also likely overstated. Many firms and institutions have recently released articles detailing how the recent surge in immigration has wreaked havoc on the systems and processes used to measure these things. Late last week, Goldman Sachs had this to say:

It seems unnecessary for the Fed to get aggressive with cuts at this point. In Powell's most recent speech, he continued to utter “data dependant,” suggesting a calculated approach. Knowing what we know now, the calculus suggests a 25bps cut in September and no further commitments for additional cuts. It’s also important to point out that it already has for those who are curious how that 25bps cut will affect mortgage rates. Today's rates have already been priced in the effect of that 25bps cut. Any additional improvement from Fed actions will come from information the market does not yet know.

Conclusion

The Fed has committed to beginning its cutting cycle. The pace and depths of the cuts are unknown. What is known is that government debt and deficit spending will continue into the foreseeable future. This creates problems for the Fed, more so the Treasury, and, of course, investors. The Treasury will continue to be very selective in the tenure of new debt issued and will do its best to supply treasury markets with liquidity support via buybacks. This careful selection in issuance will continue to influence the shape of the curve. Investors will decide if the long-term picture for US government debt is one they want to be involved in and if the reward for holding that debt justifies the long-term risks. I surmise the long end of the curve will struggle to find organic participation, and government support on the long end will be limited.